Networking Concepts

Table of Contents

Networking Resources Link to Networking Resources

Here are some valuable resources to learn about networking:

TryHackMe Modules Link to TryHackMe Modules

- Networking Concepts on TryHackMe

- Network Fundamentals Module on TryHackMe

- Introduction to Networking Module on TryHackMe

- Network Security Module on TryHackMe

- Network Security and Traffic Analysis Module on TryHackMe

External Resources Link to External Resources

- Cisco Networking Basics

- CompTIA Network+ Certification Guide

- Networking for Beginners on Udemy

- Networking Fundamentals on edX

- How the Internet Works - YouTube Video

Introduction Link to Introduction

Have you ever wondered why you need an IP address to access the Internet? Is it true that an IP address can uniquely identify the user? Are you curious to learn what the life of a packet looks like? If the answer is yes, let’s dive in!

This room is the first room in a series of four rooms dedicated to introducing the user to vital networking concepts and the most common networking protocols:

- Networking Concepts (this room)

- Networking Essentials Link

- Networking Core Protocols Link

- Networking Secure Protocols

Room Prerequisites Link to Room Prerequisites

This room expects that you know terms such as IP address and TCP port number; however, we don’t expect that the reader is able to explain such terms in proper technical depth. If you are unfamiliar with these terms, please consider joining the Pre Security path.

Learning Objectives Link to Learning Objectives

By the time you finish this room, you will have learned about the following:

- ISO OSI network model

- IP addresses, subnets, and routing

- TCP, UDP, and port numbers

- How to connect to an open TCP port from the command line

OSI Model Link to OSI Model

Before we start, we should note that the OSI model might initially seem complicated. Don’t worry if you encounter cryptic acronyms, as we provide examples of the OSI model layers. We assure you that by the time you finish this module, this task will feel like a piece of cake.

The OSI (Open Systems Interconnection) model is a conceptual model developed by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) that describes how communications should occur in a computer network. In other words, the OSI model defines a framework for computer network communications. Although this model is theoretical, it is vital to learn and understand as it helps grasp networking concepts on a deeper level. The OSI model is composed of seven layers:

- Physical Layer

- Data Link Layer

- Network Layer

- Transport Layer

- Session Layer

- Presentation Layer

- Application Layer

The numbering starts with the physical layer being layer 1, while the top layer, the application layer, is layer 7. To help you remember the layers from bottom to top, you can use a mnemonic such as “Please Do Not Throw Spinach Pizza Away.” You can check the Internet for other easy-to-remember acronyms if this helps you memorize them. Remembering the OSI model layers with their layer numbers is important; otherwise, you will struggle to understand terms such as “layer 3 switch” or “layer 7 firewall.”

The Seven Layers of the OSI Model Link to The Seven Layers of the OSI Model

Layer 1: Physical Layer Link to Layer 1: Physical Layer

The physical layer, also referred to as layer 1, deals with the physical connection between devices; this includes the medium, such as a wire, and the definition of the binary digits 0 and 1. Data transmission can be via an electrical, optical, or wireless signal. Consequently, we need data cables or antennas, depending on our physical medium.

Examples of the physical layer medium include Ethernet cable, optical fiber cable, and WiFi radio bands (2.4 GHz, 5 GHz, 6 GHz).

Layer 2: Data Link Layer Link to Layer 2: Data Link Layer

The data link layer, i.e., layer 2, represents the protocol that enables data transfer between nodes on the same network segment. This layer describes an agreement between different systems on how to communicate. For example, a company office with ten computers connected to a network switch represents a network segment.

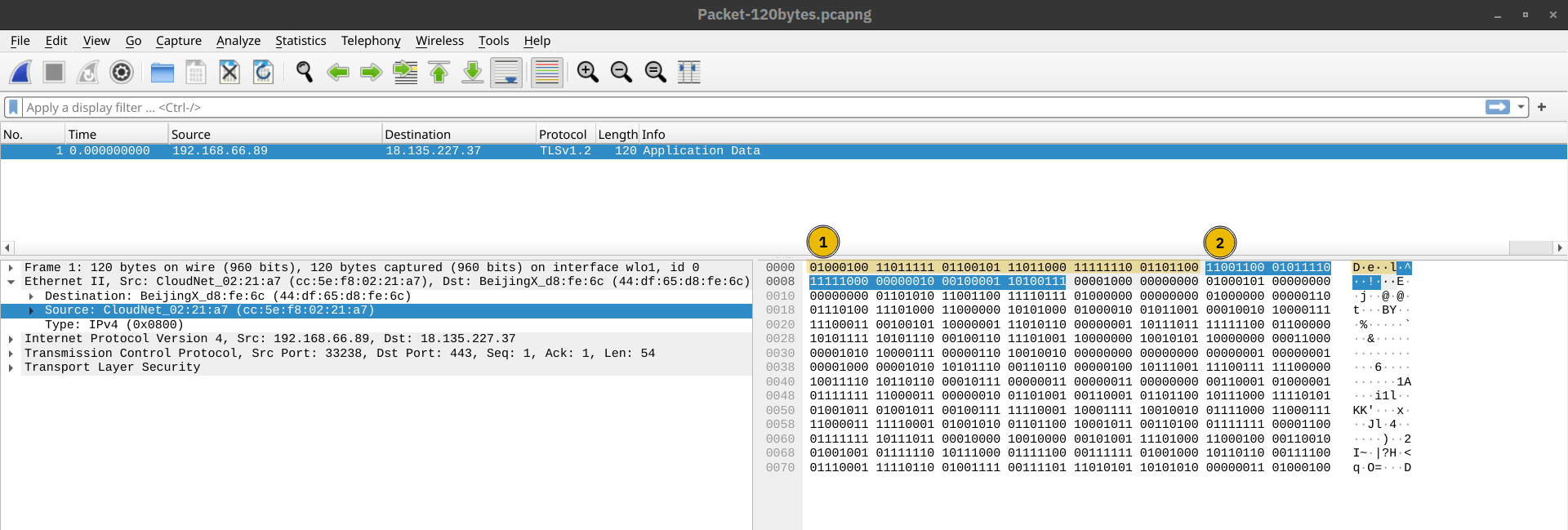

Examples of layer 2 include Ethernet (802.3) and WiFi (802.11). Ethernet and WiFi addresses are called MAC addresses (Media Access Control), expressed in hexadecimal format. A MAC address consists of six octets, where the three leftmost bytes identify the vendor. We expect to see two MAC addresses in each frame in real network communication over Ethernet or WiFi. The packet in the screenshot below shows:

- The destination data-link address (MAC address) highlighted in yellow

- The source data link address (MAC address) is highlighted in blue

- The remaining bits show the data being sent

Layer 3: Network Layer Link to Layer 3: Network Layer

The network layer, i.e., layer 3, is concerned with sending data between different networks. It handles logical addressing and routing, i.e., finding a path to transfer the network packets between diverse networks.

Examples of the network layer include Internet Protocol (IP), Internet Control Message Protocol (ICMP), and Virtual Private Network (VPN) protocols such as IPSec and SSL/TLS VPN.

Layer 4: Transport Layer Link to Layer 4: Transport Layer

Layer 4, the transport layer, enables end-to-end communication between running applications on different hosts. It supports functions like flow control, segmentation, and error correction.

Examples of layer 4 are Transmission Control Protocol (TCP) and User Datagram Protocol (UDP).

Layer 5: Session Layer Link to Layer 5: Session Layer

The session layer is responsible for establishing, maintaining, and synchronizing communication between applications running on different hosts. It negotiates necessary parameters for the session and ensures data synchronization.

Examples of the session layer are Network File System (NFS) and Remote Procedure Call (RPC).

Layer 6: Presentation Layer Link to Layer 6: Presentation Layer

The presentation layer ensures data is delivered in a form the application layer can understand. It handles data encoding, compression, and encryption.

Standards at the presentation layer include character encoding (ASCII, Unicode) and file formats (JPEG, GIF, PNG). MIME (Multipurpose Internet Mail Extensions) is often used to encode binary files.

Layer 7: Application Layer Link to Layer 7: Application Layer

The application layer provides network services directly to end-user applications. Examples include protocols like HTTP, FTP, DNS, POP3, SMTP, and IMAP.

Summary Link to Summary

Reading about the ISO OSI model for the first time can be intimidating; however, it becomes easier as you progress in your study of networking protocols.

OSI Model Summary Table Link to OSI Model Summary Table

| Layer Number | Layer Name | Main Function | Example Protocols and Standards |

|---|---|---|---|

| Layer 7 | Application layer | Providing services and interfaces to applications | HTTP, FTP, DNS, POP3, SMTP, IMAP |

| Layer 6 | Presentation layer | Data encoding, encryption, and compression | Unicode, MIME, JPEG, PNG, MPEG |

| Layer 5 | Session layer | Establishing, maintaining, and synchronizing sessions | NFS, RPC |

| Layer 4 | Transport layer | End-to-end communication and data segmentation | UDP, TCP |

| Layer 3 | Network layer | Logical addressing and routing between networks | IP, ICMP, IPSec |

| Layer 2 | Data link layer | Reliable data transfer between adjacent nodes | Ethernet (802.3), WiFi (802.11) |

| Layer 1 | Physical layer | Physical data transmission media | Electrical, optical, and wireless signals |

TCP/IP Model Link to TCP/IP Model

Now that we have covered the conceptual ISO OSI model, it is time to study an implemented model, the TCP/IP model. TCP/IP stands for Transmission Control Protocol/Internet Protocol and was developed in the 1970s by the Department of Defense (DoD).

I hear you ask why the DoD would create such a model. One of the strengths of this model is that it allows a network to continue to function as parts of it are out of service, for instance, due to a military attack. This capability is possible in part due to the design of the routing protocols to adapt as the network topology changes.

In our presentation of the ISO OSI model, we went from bottom to top, from layer 1 to layer 7. In this task, let’s look at things from a different perspective, from top to bottom. From top to bottom, we have:

- Application Layer: The OSI model application, presentation, and session layers (i.e., layers 5, 6, and 7) are grouped into the application layer in the TCP/IP model.

- Transport Layer: This is layer 4.

- Internet Layer: This is layer 3. The OSI model’s network layer is called the Internet layer in the TCP/IP model.

- Link Layer: This is layer 2.

TCP/IP Model vs. ISO/OSI Model Link to TCP/IP Model vs. ISO/OSI Model

The table below shows how the TCP/IP model layers map to the ISO/OSI model layers.

| Layer Number | ISO OSI Model | TCP/IP Model (RFC 1122) | Protocols |

|---|---|---|---|

| 7 | Application Layer | Application Layer | HTTP, HTTPS, FTP, POP3, SMTP, IMAP, Telnet, SSH |

| 6 | Presentation Layer | ||

| 5 | Session Layer | ||

| 4 | Transport Layer | Transport Layer | TCP, UDP |

| 3 | Network Layer | Internet Layer | IP, ICMP, IPSec |

| 2 | Data Link Layer | Link Layer | Ethernet 802.3, WiFi 802.11 |

| 1 | Physical Layer |

Many modern networking textbooks show the TCP/IP model as five layers instead of four. For example, in Computer Networking: A Top-Down Approach (8th Edition) by Kurose and Ross, the following five-layer Internet protocol stack is described, including the physical layer:

- Application

- Transport

- Network

- Link

- Physical

In the following tasks, we will cover the IP protocol from the Internet layer and the UDP and TCP protocols from the transport layer.

IP Addresses and Subnets Link to IP Addresses and Subnets

When you hear the word IP address, you might think of an address like 192.168.0.1 or something less common, such as 172.16.159.243. In both cases, you are right. Both of these are IP addresses; IPv4 (IP version 4) addresses to be specific.

Every host on the network needs a unique identifier for other hosts to communicate with him. Without a unique identifier, the host cannot be found without ambiguity. When using the TCP/IP protocol suite, we need to assign an IP address for each device connected to the network.

One analogy of an IP address is your home postal address. Your postal address allows you to receive letters and parcels from all over the world. Furthermore, it can identify your home without ambiguity; otherwise, you cannot shop online!

As you might already know, we have IPv4 and IPv6 (IP version 6). IPv4 is still the most common, and whenever you come across a text mentioning IP without the version, we expect them to mean IPv4.

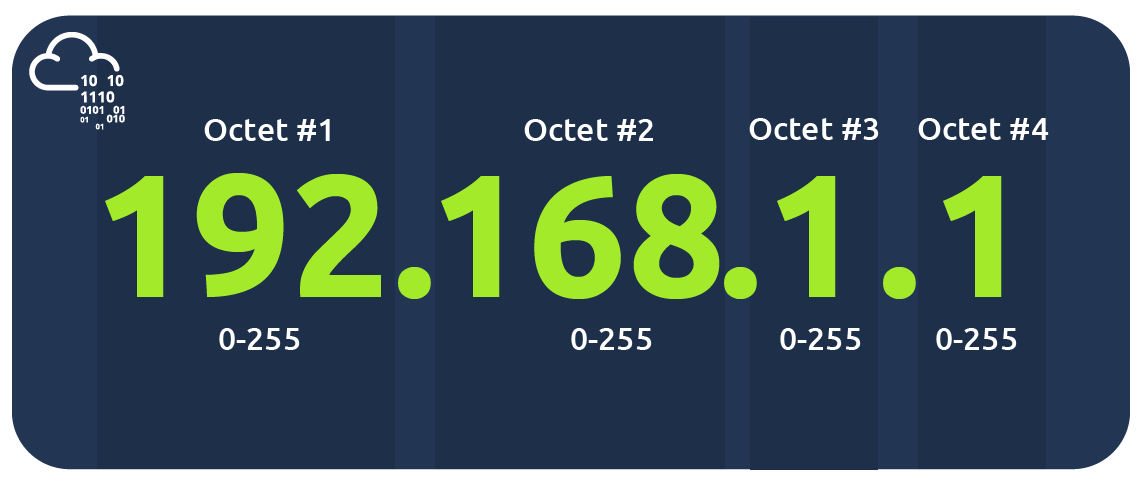

So, what makes an IP address? An IP address comprises four octets, i.e., 32 bits. Being 8 bits, an octet allows us to represent a decimal number between 0 and 255. An IP address is shown in the image below.

An IP address is made up of 4 octets or bytes and each octet represents a decimal number between 0 and 255.

At the risk of oversimplifying things, the 0 and 255 are reserved for the network and broadcast addresses, respectively. In other words, 192.168.1.0 is the network address, while 192.168.1.255 is the broadcast address. Sending to the broadcast address targets all the hosts on the network. With simple math, you can conclude that we cannot have more than 4 billion unique IPv4 addresses. If you are curious about the math, it is approximately 232 because we have 32 bits. This number is approximate because we didn’t consider network and broadcast addresses.

Looking Up Your Network Configuration Link to Looking Up Your Network Configuration

You can look up your IP address on the MS Windows command line using the command ipconfig. On Linux and UNIX-based systems, you can issue the command ifconfig or ip address show, which can be typed as ip a s. In the terminal window below, we show ifconfig.

1234567891011user@TryHackMe$ ifconfig

[...]

wlo1: flags=4163<UP,BROADCAST,RUNNING,MULTICAST> mtu 1500

inet 192.168.66.89 netmask 255.255.255.0 broadcast 192.168.66.255

inet6 fe80::73e1:ca5e:3f93:b1b3 prefixlen 64 scopeid 0x20<link>

ether cc:5e:f8:02:21:a7 txqueuelen 1000 (Ethernet)

RX packets 19684680 bytes 18865072842 (17.5 GiB)

RX errors 0 dropped 364 overruns 0 frame 0

TX packets 14439678 bytes 8773200951 (8.1 GiB)

TX errors 0 dropped 0 overruns 0 carrier 0 collisions 0

The terminal output above indicates the following:

- The host (laptop) IP address is 192.168.66.89

- The subnet mask is 255.255.255.0

- The broadcast address is 192.168.66.255 Let’s use ip a s to compare how the network card IP address is presented.

123456789user@TryHackMe$ ip a s

[...]

4: wlo1: <BROADCAST,MULTICAST,UP,LOWER_UP> mtu 1500 qdisc noqueue state UP group default qlen 1000

link/ether cc:5e:f8:02:21:a7 brd ff:ff:ff:ff:ff:ff

altname wlp3s0

inet 192.168.66.89/24 brd 192.168.66.255 scope global dynamic noprefixroute wlo1

valid_lft 36795sec preferred_lft 36795sec

inet6 fe80::73e1:ca5e:3f93:b1b3/64 scope link noprefixroute

valid_lft forever preferred_lft forever

The terminal output above indicates the following:

- The host (laptop) IP address is 192.168.66.89/24

- The broadcast address is 192.168.66.255 If you are wondering, a subnet mask of 255.255.255.0 can also be written as /24. The /24 means that the leftmost 24 bits within the IP address do not change across the network, i.e., the subnet. In other words, the leftmost three octets are the same across the whole subnet; therefore, we can expect to find addresses that range from 192.168.66.1 to 192.168.66.254. Similar to what was mentioned earlier, 192.168.66.0 and 192.168.66.255 are the network and broadcast addresses, respectively.

Private Addresses Link to Private Addresses

As we are explaining IP addresses, it is useful to mention that for most practical purposes, there are two types of IP addresses:

Public IP addresses

Private IP addresses RFC 1918 defines the following three ranges of private IP addresses:

10.0.0.0 - 10.255.255.255 (10/8)

172.16.0.0 - 172.31.255.255 (172.16/12)

192.168.0.0 - 192.168.255.255 (192.168/16)

We presented earlier an analogy stating that a public IP address is like your home postal address. A private IP address is different; the original idea is that it cannot reach or be reached from the outside world. It is like an isolated city or a compound, where all houses and apartments are numbered systematically and can easily exchange mail with each other, but not with the outside world. For a private IP address to access the Internet, the router must have a public IP address and must support Network Address Translation (NAT). At this stage, let’s not worry about understanding how NAT works, as we will revisit it later in this module.

Before moving on, I recommend memorising the private IP address ranges. Otherwise, you might see an IP address such as 10.1.33.7 or 172.31.33.7 and try to access it from a public IP address.

Routing Link to Routing

A router is like your local post office; you hand them the mail parcel, and they would know how to deliver it. If we dig deeper, you might mail something to an address in another city or country. The post office will check the address and decide where to send it next. For example, if it is to leave the country, we expect one central office to handle all shipments abroad.

In technical terms, a router forwards data packets to the proper network. Usually, a data packet passes through multiple routers before it reaches its final destination. The router functions at layer 3, inspecting the IP address and forwarding the packet to the best network (router) so the packet gets closer to its destination.

A computer network diagram showing a web server, a mobile user with a laptop, and an office user with a desktop computer. There are six routers between the three systems and there are different paths that a packet can use to travel from one system to the other.

UDP and TCP Link to UDP and TCP

The IP protocol allows us to reach a destination host on the network; the host is identified by its IP address. We need protocols that enable processes on networked hosts to communicate with each other. There are two transport protocols to achieve that: UDP and TCP.

UDP Link to UDP

UDP (User Datagram Protocol) allows us to reach a specific process on the target host. UDP is a simple connectionless protocol that operates at the transport layer (i.e., layer 4). Being connectionless means that it does not need to establish a connection and does not provide a mechanism to confirm that the packet has been delivered.

An IP address identifies the host, but we also need a mechanism to determine the sending and receiving process. This can be achieved using port numbers, which use two octets and range between 1 and 65535; port 0 is reserved. (The number 65535 is calculated by the expression (2^16 - 1).)

A real-life example similar to UDP is the standard mail service, which does not provide delivery confirmation. In other words, there is no guarantee that the UDP packet has been successfully received, similar to sending a parcel via standard mail without confirmation of delivery. In standard mail, this results in a cheaper cost compared to delivery options with confirmation. In the case of UDP, it translates to better speed than a transport protocol that provides “confirmation.”

But what if we want a transport protocol that acknowledges received packets? The answer lies in using TCP instead of UDP.

TCP Link to TCP

TCP (Transmission Control Protocol) is a connection-oriented transport protocol. It uses various mechanisms to ensure reliable data delivery between different processes on the networked hosts. Like UDP, TCP is also a layer 4 protocol. However, being connection-oriented, it requires the establishment of a TCP connection before any data can be sent.

In TCP, each data octet has a sequence number, making it easy for the receiver to identify lost or duplicated packets. The receiver acknowledges the reception of data with an acknowledgment number specifying the last received octet.

A TCP connection is established using what’s called a three-way handshake. Two flags are used: SYN (Synchronize) and ACK (Acknowledgment). The packets are exchanged as follows:

- SYN Packet: The client initiates the connection by sending a SYN packet to the server. This packet contains the client’s randomly chosen initial sequence number.

- SYN-ACK Packet: The server responds to the SYN packet with a SYN-ACK packet, which includes the initial sequence number randomly chosen by the server.

- ACK Packet: The three-way handshake is completed as the client sends an ACK packet to acknowledge the reception of the SYN-ACK packet.

The TCP three-way handshake requires the exchange of three packets.

Similar to UDP, TCP identifies the process of initiating or waiting (listening) for a connection using port numbers. A valid port number ranges between 1 and 65535 because it uses two octets, and port 0 is reserved.

Encapsulation Link to Encapsulation

Before wrapping up, it is crucial to explain another key concept: encapsulation. In this context, encapsulation refers to the process where each layer adds a header (and sometimes a trailer) to the received unit of data and sends the “encapsulated” unit to the layer below.

Encapsulation is essential as it allows each layer to focus on its intended function. Below are the four steps involved:

Application Data: It all starts when the user inputs the data they want to send into the application. For example, you might write an email or an instant message and hit the send button. The application formats this data and starts sending it according to the application protocol used, using the layer below it, the transport layer.

Transport Protocol Segment or Datagram: The transport layer (such as TCP or UDP) adds the proper header information and creates the TCP segment (or UDP datagram). This segment is sent to the layer below it, the network layer.

Network Packet: The network layer (i.e., the Internet layer) adds an IP header to the received TCP segment or UDP datagram. This IP packet is then sent to the layer below it, the data link layer.

Data Link Frame: The Ethernet or WiFi layer receives the IP packet and adds the proper header and trailer, creating a frame.

The process can be summarized as follows:

- Application data is encapsulated within a TCP segment or UDP datagram.

- The TCP segment or UDP datagram is encapsulated within an IP packet.

- The IP packet is encapsulated within a data link frame.

This encapsulation process must be reversed on the receiving end until the application data is extracted.

The Life of a Packet Link to The Life of a Packet

Based on what we have studied so far, we can explain a simplified version of a packet’s life. Let’s consider the scenario where you search for a room on TryHackMe:

- On the TryHackMe search page, you enter your search query and hit enter.

- Your web browser, using HTTPS, prepares an HTTP request and pushes it to the layer below it, the transport layer.

- The TCP layer needs to establish a connection via a three-way handshake between your browser and the TryHackMe web server. After establishing the TCP connection, it can send the HTTP request containing the search query. Each TCP segment created is sent to the layer below it, the Internet layer.

- The IP layer adds the source IP address (i.e., your computer) and the destination IP address (i.e., the IP address of the TryHackMe web server). For this packet to reach the router, your laptop delivers it to the layer below it, the link layer.

- Depending on the protocol, the link layer adds the proper link layer header and trailer, and the packet is sent to the router.

- The router removes the link layer header and trailer, inspects the IP destination, among other fields, and routes the packet to the proper link. Each router repeats this process until it reaches the router of the target server.

- The steps will then be reversed as the packet reaches the router of the destination network.

As we cover additional protocols, we will revisit this exercise and create a more in-depth version.

Telnet Link to Telnet

Start Machine Link to Start Machine

- Click on the Start AttackBox button at the top.

- Click on the Start VM button on the right to start the attached virtual machine (VM). Give both machines about 2 minutes each to properly boot up.

Once the two machines are ready, we need to start the terminal on the AttackBox to experiment with Telnet.

What is Telnet? Link to What is Telnet?

The TELNET (Teletype Network) protocol is a network protocol for remote terminal connection. In simpler terms, Telnet allows you to connect to and communicate with a remote system and issue text commands. Although initially used for remote administration, you can use Telnet to connect to any server listening on a TCP port number.

Target Virtual Machine Services Link to Target Virtual Machine Services

On the target virtual machine, different services are running. We will experiment with three of them:

- Echo Server: This server echoes everything you send it. By default, it listens on port 7.

- Daytime Server: This server listens on port 13 by default and replies with the current day and time.

- Web (HTTP) Server: This server listens on TCP port 80 by default and serves web pages.

Note: The echo and daytime servers are considered security risks and should not be run; however, we started them explicitly to demonstrate communication with the server using Telnet.

Connecting with Telnet Link to Connecting with Telnet

In the terminal below, connect to the target VM at the echo server’s TCP port number 7. To close the connection, press the CTRL + ] keys simultaneously.

123456789101112131415user@TryHackMe$ telnet MACHINE_IP 7

telnet MACHINE_IP 7

Trying MACHINE_IP...

Connected to MACHINE_IP.

Escape character is '^]'.

Hi

Hi

How are you?

How are you?

Bye

Bye

^]

telnet> quit

Connection closed.

In the terminal below, we use telnet to connect to the daytime server listening at port 13. We noticed that the connection closes once the current date and time are returned.

123456user@TryHackMe$ telnet MACHINE_IP 13

Trying MACHINE_IP...

Connected to MACHINE_IP.

Escape character is '^]'.

Thu Jun 20 12:36:32 PM UTC 2024

Connection closed by foreign host.

Finally, let’s request a web page using telnet. After connecting to port 80, you need to issue the command GET / HTTP/1.1 and identify the host where anything goes, such as Host: telnet.thm. The output below shows the exchange. (The page has been redacted.)

Note: You may have to press Enter after sending the information in case you don’t get a response.

123456789101112user@TryHackMe$ telnet MACHINE_IP 80

Trying MACHINE_IP...

Connected to MACHINE_IP.

Escape character is '^]'.

GET / HTTP/1.1

Host: telnet.thm

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Content-Type: text/html

[...]

Connection closed by foreign h

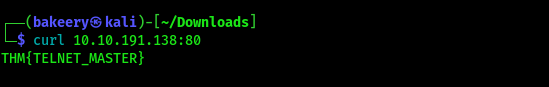

to get the flag, as mentioned above the websever listens on port 80, therefore we run telnet MACHINE IP 80 in my case its,

1telnet 10.10.191.138 80

i got served content content as:

123456789101112131415161718192021222324 telnet 10.10.191.138 80

Trying 10.10.191.138...

Connected to 10.10.191.138.

Escape character is '^]'.

HTTP/1.0 400 Bad Request

Content-Type: text/html

Content-Length: 345

Connection: close

Date: Tue, 22 Oct 2024 16:25:09 GMT

Server: *******

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="iso-8859-1"?>

<!DOCTYPE html PUBLIC "-//W3C//DTD XHTML 1.0 Transitional//EN"

"http://www.w3.org/TR/xhtml1/DTD/xhtml1-transitional.dtd">

<html xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1999/xhtml" xml:lang="en" lang="en">

<head>

<title>400 Bad Request</title>

</head>

<body>

<h1>400 Bad Request</h1>

</body>

</html>

Connection closed by foreign host.

The server name and the version can be seen but the flag is not there, i was having trouple with the connection, then i use curl to obatined the flag.

curl is a command-line tool used to transfer data to or from a server using various protocols, including HTTP, HTTPS, FTP, and more. It allows users to send requests and receive responses, making it useful for testing APIs, downloading files, and performing network diagnostics. With its numerous options, curl can handle tasks like authentication, data formatting, and custom headers.Conclusion Link to Conclusion

In this room, we covered the ISO OSI and TCP/IP models, comparing and contrasting the two. We also covered IP addresses and subnets, briefly explaining routing. Furthermore, after diving into TCP and UDP, we explained encapsulation. For demonstration purposes, we used telnet to “talk” to different servers over TCP.

Now that you have finished Networking Concepts, it is time to join

Networking Concepts

© EveSunMaple | CC BY-SA 4.0